The Mad Agriculture Journal

In San Luis, a vision of rebirth for a once-bustling downtown

Published on

July 08, 2022

Written by

Mary Slosson & Gregor MacGregor

Photos by

Sophia Piña-McMahon & Gregor MacGregor

San Luis, Colorado – It’s early May, and the snow on the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the east has already largely receded. We’re in San Luis – the oldest town in Colorado – where the community marks the spring snowmelt by the emergence of a bird on Culebra Peak. Not an actual bird, but a snowfield that melts into the shape of a winged creature that doesn’t emerge until August in good water years.

The early snowmelt feels like a harbinger of change, much like the empty storefronts that line Main Street. Once occupied by coffee shops, dance halls and bars, many of the stucco buildings that line the main thoroughfare are now crumbling, the signs advertising the bygone era now wind-worn and faded. Small, rural towns like San Luis have been uniquely impacted by a string of historical trends: younger generations leaving small towns for urban centers like Denver, the economics of farming in the valley shifting such that fewer crops can be grown profitably, and the impacts of a state wracked by drought and water scarcity that serve as an existential weight, ever-present and looming in the background.

Enter Ronda Lobato, a seventh-generation resident of San Luis. Her roots run deep in the community and in the land. Both she and her husband can find their lineage among the founding families of San Luis. She grew up swimming in the irrigation ditches of her family’s ranch and catching horses to ride beneath the mountain.

“As the first settlers came in, downtown San Luis has always been the centerpoint. There were a lot more people back then. As the agricultural industry started dwindling, so did the people,” Lobato said.

The population of San Luis and the surrounding villages used to be over 6,000 people. Now, it’s roughly 600. The school used to have 100 children in a class. This year, six students are graduating from the high school. Where once Costilla County was a hub for spinach and lettuce, with thousands of acres dedicated to growing vegetables, now the primary crops grown are alfalfa and oats for cattle. The fundamental economics of agriculture have changed.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic began, and in a paradoxical way it started to change the trajectory of the community, Lobato said. Her own daughter had been planning to leave for a big city, but the public health crisis changed her mind.

“Now, I think a lot more of our youth are wanting to stay,” Lobato said. “It really made them realize what we have here in our community, and not wanting to leave. We’re self-sustaining here. We don’t have to worry about going to the grocery store if we absolutely don’t have to. We have our farm, and the girls have been raised on the land with our water.”

Her vision for revitalizing downtown San Luis is part and parcel of wanting to convince the younger generations that San Luis is a community and a town worth investing in and laying down roots.

On a recent morning, Lobato showed us the parcel of land that she acquired last year in the heart of downtown. The property was once the San Luis State Bank, the first bank in the town of San Luis. Dating back to the early 1900s, it still has the original vault with a hefty old safe inside.

The building’s ceiling has collapsed, and through the windows you can see abandoned knick-knacks covered in dust, a time capsule from the town’s past. The stucco facade has started to crack, revealing adobe brick underneath.

But Lobato has a vision of what this property could be, and is determined to use it to help revitalize downtown San Luis. In her mind are blueprints for a cluster of new ventures that could breathe new life into the block. Where the bank once operated, she wants to open a speakeasy called The Vault, incorporating the massive metal vault that gleams in the back of the building, now partially obscured by collapsed beams from the ceiling. The speakeasy would incorporate the historical story of San Luis.

After completing a community needs assessment, Lobato also plans on bringing a bakery, a community space for youth, and affordable housing to the parcel.

“Our community has very limited social spaces, and that really takes a toll on our mental health. We’re not socializing, we’re not communicating, we’re not together as a community, and it’s really separated people in our community,” Lobato said. A community space would harken back to the town’s heyday, when it had a movie theater and other communal spaces that helped everyone stay connected.

A broader community of bakers and farmers have volunteered their expertise to establish the local economy Ronda envisions. The Bread Bakers Guild of America and the Colorado Grain Chain have both donated memberships to connect Ronda with like-minded restaurateurs and farmers. Andy Clark, the heritage grain and artisan bread aficionado of Moxie Bread Company has offered to help with the physical layout of the bakery, while The Culinary Institute of America has provided a partial scholarship to attend one of their bread baking boot camps.

Lobato formed an LLC called Lupine Luna with her daughters to make the vision a reality. They have a business plan and a convincing vision. Now they just need money and time to make it happen.

A town defined by water

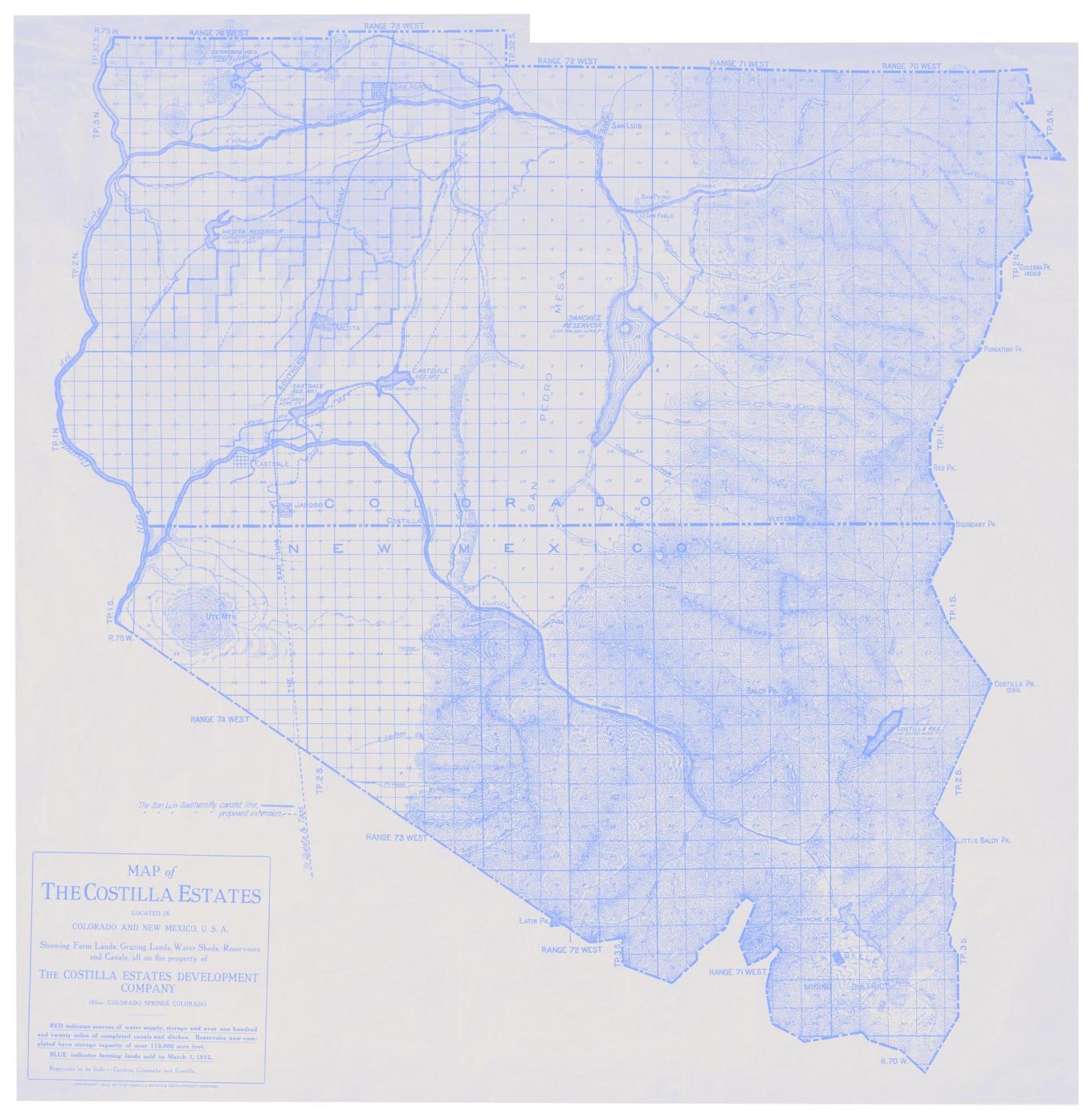

San Luis is a community shaped by the unique agricultural system imported by Spanish and Mexican settlers to the Southwest, centered around irrigation ditches called ‘acequias.’ But acequias are more than just a water delivery system, they represent a culture and form of governance rooted in equity and fairness, expressed in the requirement that labor on the ditch is shared and in the ability of each family to cast a single vote, regardless of the amount of land or water they use. While the situation on each acequia today may be different from the historical mold, the core importance of community remains.

Equitable governance was born out of the similarly arid climate in Spain and North Africa – the word acequia is Arabic for ‘water bearer’ – and played a crucial role in the establishment of cities like Santa Fe, Taos, and San Luis. In the countryside, each irrigator in a newly established community received land in the form of a vara strip, a stretch of land roughly 50 yards wide by 2 miles long. Each vara strip provides access to a stream or the acequia, space for growing irrigated crops, land for a home, and space for a small cattle holding. The strips were arrayed to maximize the return flow of water to other parciantes on the ditch and promote communal self-sufficiency on the frontier.

Acequias were also crucial for new town residents, as town ditches supplied the water for gardens, orchards, and domestic use. The Montez Ditch serves this purpose in San Luis and residents see its revitalization paired with the revitalization of the town itself.

For the last eight years, the Montez has been working with the Acequia Assistance Project at the University of Colorado Law School to reestablish its role at the heart of the town. Students and attorneys worked with members of the Montez’ comisión to draft bylaws, incorporate the ditch, and examine who owned rights on the ditch and where water had historically been used. The work is necessary because as the town has grown, portions of the ditch were paved over and getting water to all of the parciantes became increasingly difficult.

Members of the Montez, including Ronda, see the full reestablishment and beautification of the ditch as a way to proudly display the town’s acequia heritage and provide a classic western amenity: flowing water.

Charlie Jacquez, who served as a member of the Montez comisión and can recount the town’s history from memory, noted that the ditch once crossed main street from the east to the west side of town before it was paved over in the 1930s when main street became state highway 159. Jacquez and others would love to see the free-flowing ditch come back to life, harkening back to San Luis’ vibrant past self.

“San Luis was made out of dirt in those days. Now it’s pavement and concrete, so the distribution is tougher,” Jacquez said. “We’ll figure out a way to get water to that other side of town. I think that would be cool. Go to Gunnison, you’ll see ditches running right through town. It’s really neat… It’s kinda magic.”

Looking Forward

These days, Lobato is simultaneously reaching into the past and looking towards the future. She’s personally witnessed the town shrink and storefronts shut down as the younger generation abandons rural life for bigger cities. Because of this, her next steps are planned with her daughters and their future in mind – by pulling on a string from her past.

After graduating high school, Lobato started her own baking company, where she decorated wedding cakes. Years later, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, she shared her love of baking with her three daughters Faleen, 24, Feliciana, 19, and Josephina, 13. And now, she wants to help create a future in San Luis where her daughters are not driven to leave in order to have economic and employment opportunities.

“I want my family to stay here and live that legacy that our founding fathers brought,” Lobato said.

Lupine Luna has garnered technical and financial support from the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority Small-Scale Housing Technical Assistance pilot program, the Costilla County Economic Development Council, the San Luis Valley Small Business Development Center, the San Luis Valley Housing Coalition, the Costilla County Department of Social Services, and the Rocky Mountain Service Employment Redevelopment, among others. To donate expertise or assist Lupine Luna in making their vision a reality, contact lupinelunallc@gmail.com.