The Mad Agriculture Journal

Boulder Heirloom Apples

Published on

June 01, 2020

Written by

Dustin Bailey

Photos by

Dustin Bailey

Boulder, Colorado is typically seen as an outdoor enthusiasts paradise, but this place has a surprising history of agricultural significance. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, gold lured prospectors and their families from all over the country to Colorado. As families started moving to Boulder, they also brought their favorite varieties of fruit trees from the Midwest, the South, and the Northeast. Soon enough, orchards began popping up and Colorado became one of the top apple-growing states. People around the country raved about the unique apples coming from Colorado. Today, that bit of history is lost from most Coloradans. The remnant apple trees around Boulder are withering away and with them, incredible tales and legends about American history.

During this apple boom in Colorado, a new cultivar was being created in Washington that was incredibly deep crimson red, had an extended shelf life, resistant to disease and pests, was incredible for industrial scale orchards, but tasted like cardboard. The introduction of Red Delicious solidified Washington’s place as the apple growing capital of the country. This was a time when premium prices were paid for the intensity of red an apple produced rather than its flavor. At the same time, orchards in Colorado were crumbling due to drought, disease, and significant drops in demand. As time went on, many of the trees in Colorado lived on without tedious pruning, irrigation, or special care. There are hundreds of these trees scattered around Boulder today. It is estimated that there are around 60 different apple varieties in Boulder that are each unique in taste, appearance, and use. These 100-year old trees are time capsules and can teach us about a much different time period of agriculture when diversification was still king.

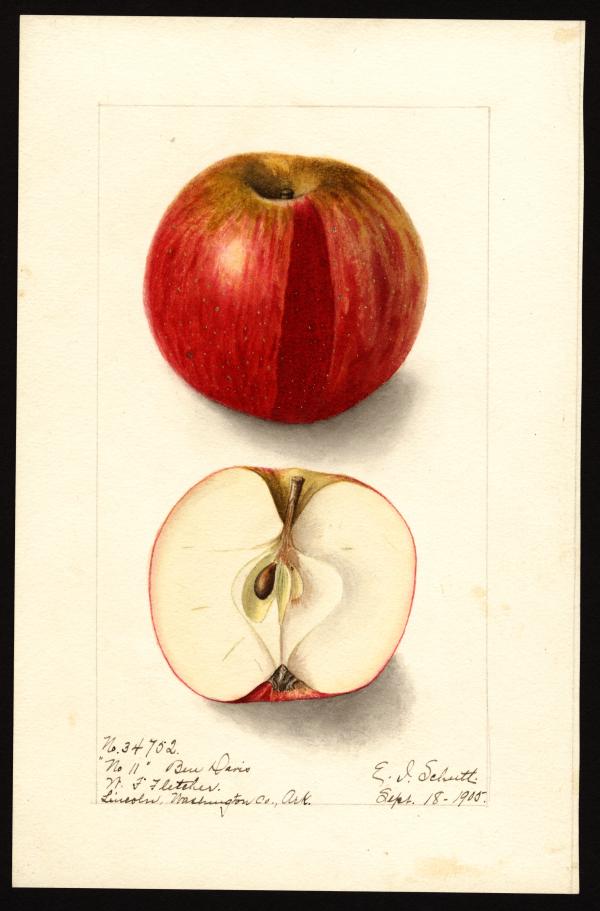

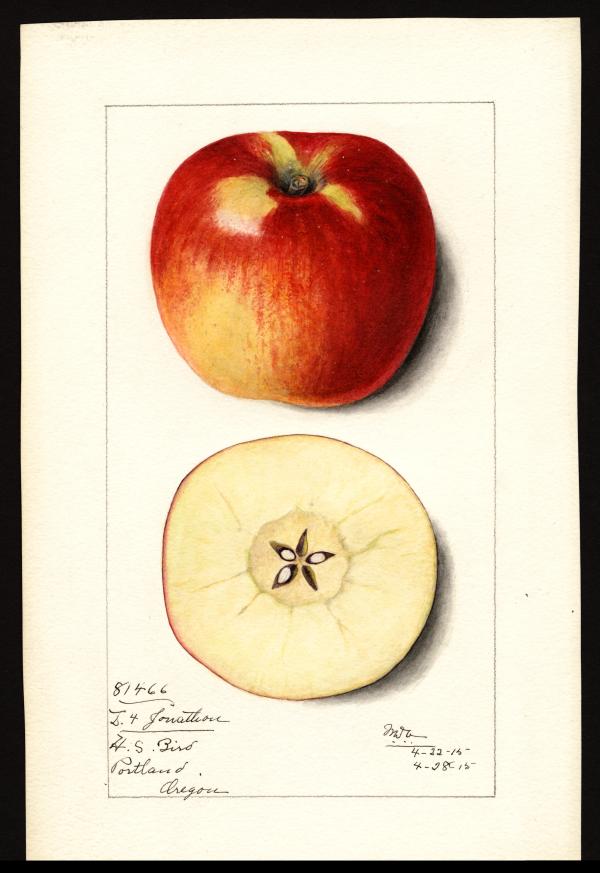

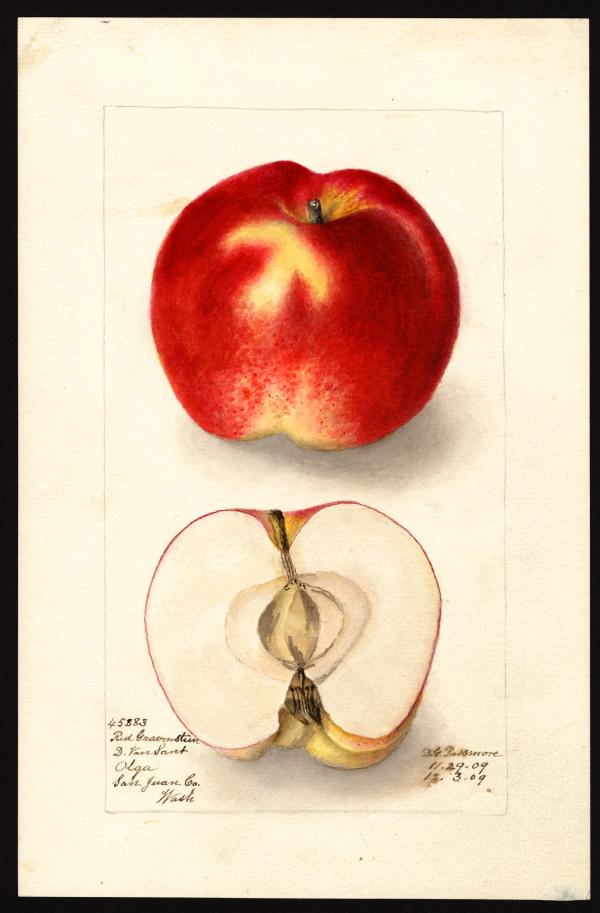

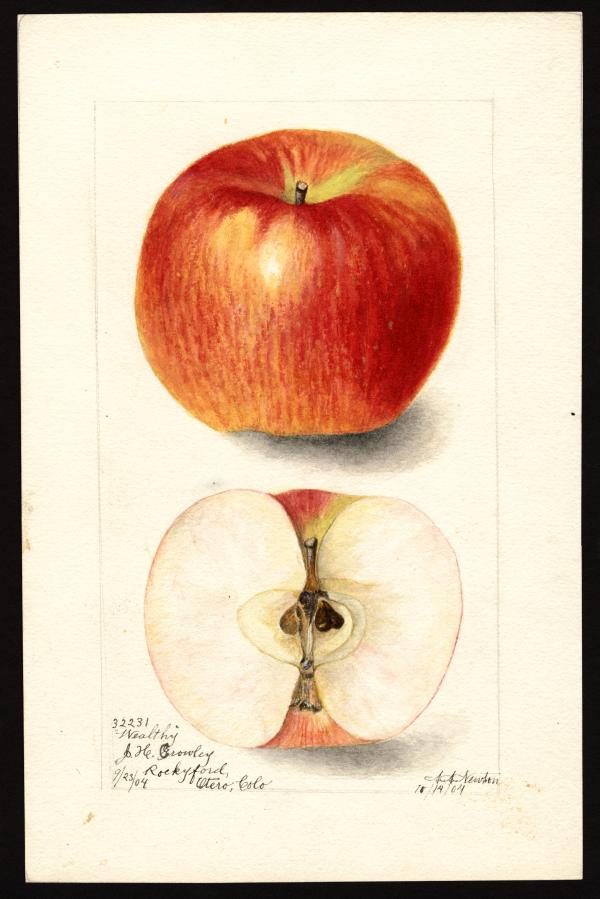

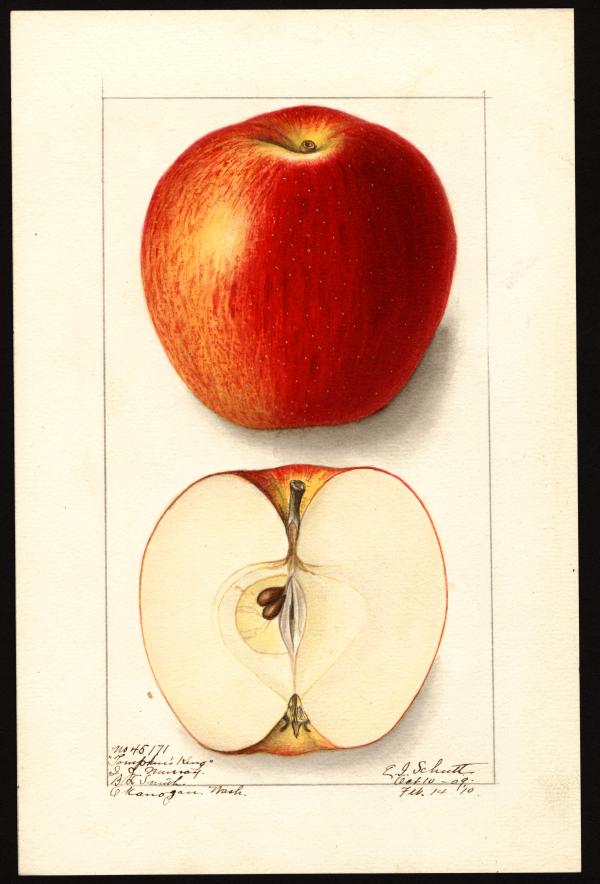

In 1905, the USDA cataloged all the known apple varieties in America and the finished product was a 400 page book of nearly 17,000 apple varieties. During this time apples were critically acclaimed, towns were named after their famous apple variety, and they were undoubtedly the fruit of America. Back then apples ranged from the size of a cherry to larger than a softball. Some varieties looked like misshapen potatoes with incredible flavor, some were striped with crimson and gold, some were deep maroon red with dots of white, some ripened in July and some wouldn’t ripen until December, some tasted like pineapple and others like cinnamon and mulled spice, some grew better in the heat and humidity of the south while others succeeded in the dry climate of Colorado. There was so much variation that there was a perfect variety for any taste, soil, or climate.

Our modern knowledge of apples is formed from the produce section of large chain grocery stores which feature the classic Red Delicious, Gala, Honeycrisp, Fuji, Granny Smith, and Golden Delicious apples. Unfortunately, as with most other produce at these grocery stores, many of these varieties are popular because of their unusually long storage capacity or uniform appearance. This is a common trope in the modern food system. The switch to efficient mass produced food in the middle of the 20th century drastically reduced the role of small farms and the need for thousands of species varieties. Why grow 50 varieties of apples in an orchard when the mass production of one variety will fill the same need with less work. As a result, we have lost hundreds, possibly thousands, of apple varieties across the country.

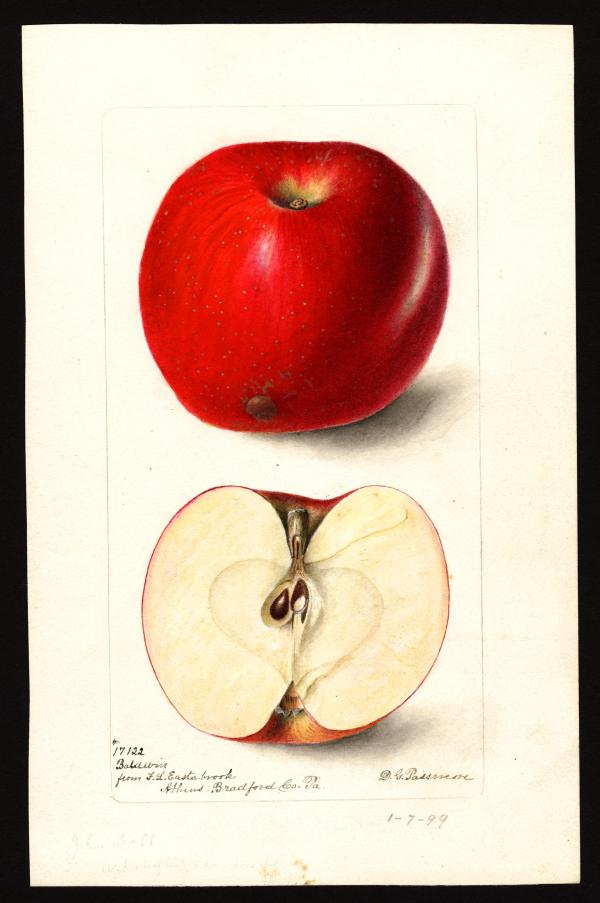

Some apples, such as the Baldwin, are known for their biennial tendencies. They will have an incredibly heavy fruit bearing year and then the next year, they will focus on vegetative growth and will produce almost no fruit. In a commercial orchard with one or two varieties, this is a business nightmare. A whole year of little to no fruit profit from the Baldwin trees. Many of these heirloom apple trees share this biennial bearing quality which is why so many weren’t considered for commercial orchards.

The Golden Russet is another example of an apple left out by profit-oriented modern standards. Golden Russet is the golden child for cider producers. A famous pomologist and connoisseur of cider once said, “If you are going to plant 100 apple trees for cider, 99 of them should be Golden Russet. The rest should be whatever you want.” Golden Russet excels in so many ways; it makes a mean pie, incredibly complex cider, and a month after picking, the flavor is unlike any apple you have ever eaten. Regardless, the Golden Russet looks like the love child of a potato, pear, and apple. It is the exact opposite of Red Delicious in every way, and has consequently lost it’s edge on the market.

Some of these heirloom apples were bred for hundreds of years to be perfect for the cider making process, some were perfectly bred for baking, and some were perfect for eating right off the tree. There are accounts of apple cultivation that go all the way back to ancient Rome: excerpts can be found in Homer’s Odyssey from 1000 BCE, Pliny the Elder wrote about apple cultivation in his well-known book Naturalis Historia, and Marcus Portio Cato wrote an in-depth guide describing fruit propagation in 150 BCE. In Christianity, the apple played a significant role in the Garden of Eden. This inevitably had an impact on the latin naming of the apple, Malus. Malus is similar to Malum meaning “evil”. Apples can be found throughout religions and myths from across the world. One of the labors of Hercules required him to pick the golden apple off the tree of life. In Norse mythology, apples are associated with the goddess of youth, Iðunn. Humans have been linked to the apple for thousands of years but the reason it is considered an American icon is because the number of varieties exploded once seeds were brought to the New World. Apples were the talk of the town in America up until the mid 1900’s. Throughout this period, trying the local apple variety was always a priority when visiting a new town.

Cider and apples have a much longer history in Europe than in North America. Cider was a popular drink in England and other parts of Europe because, in part, it was often safer to drink cider than water in many urban areas. The alcohol in the cider would kill most of the harmful bacteria and so colonists of the New World also took advantage of this quality. Up until prohibition, cider was a favorite drink in America. Once prohibition hit, the government quelled production by cutting down many of these cider trees. Yet again, America lost more unique varieties of apples.

We can thank a few people in American history for the spread of all these apple varieties but one individual in particular has found a place in American folklore for his involvement in bringing apples out west. John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed, was an apple enthusiast and missionary. He started his first orchard in Pennsylvania with seeds collected from a local cider mill. When pioneers began heading west, John decided he would head down the Ohio River with a boat full of apple seeds. John was part of a Christian denomination called “Swedenborgian” which, at first glance, seems like a more ecologically oriented theology than the more traditional orthodox denominations. John didn’t believe in grafting because it seemed morbid to him which is why he stuck to spreading apple trees by seed. John is likely responsible for creating hundreds, maybe thousands, of apple varieties in his lifetime by planting seeds throughout the country.

If you are familiar with apple reproduction, you know that planting an apple seed does not result in the same variety of fruit tree. For example, if you eat a honeycrisp apple, take a seed, and plant it, the tree that grows will likely taste, look, and grow differently than a honeycrisp apple. So imagine John floating down the Ohio River, scouting routes for pioneers, and planting apple seeds. Once the trees were a year or two old, he would dig them up and give or sell them to settlers. Each one of these trees was its own variety with eventual destinations spread all across the country.

Without this background, the apple pie as our national dish is a passing fact. But this pie holds the history of heirloom apples in our country. Luckily, there are still people cultivating and reviving heirloom varieties and cultural practices. These varieties were bred before the industrialization of our food system and can teach us important lessons about sustainable agriculture practices.

The apple trees that are left standing today in Boulder are typically around 100 years old, leaving us with a set of genetics that can provide a glimpse into their specialty, use and patterns. Unfortunately, due to old age, we are starting to lose these heirloom varieties at an alarming rate. With the push toward more diverse and holistic food systems, these heirloom apples have once again garnered some support. Home gardeners and farmers alike have begun to see the value in multiple varieties. On a practical level, orchard diversity can prevent the devastating realities of many pests in the region. The name of the game with biodynamic and biological farming is not pesticide use or fertilizer use but rather promoting diversity and soil health. Some apple varieties are susceptible to a devastating disease called fire blight. If you have an orchard of one apple variety, a bout with fire blight can be entirely destructive. Diversity can prevent the spread of disease, as some varieties may have a resistance.

The tide is turning for America’s food production, with movement toward species rich systems. Understanding the wisdom gathered and species cultivated from generations past will be a critical piece of the challenge ahead. Not only for bringing back incredible tastes and flavors, but also for preserving the history and regional needs associated with each variety. The apple trees of Boulder have withstood the shifting agricultural landscape of the last 100 years. Preserving and continuing the legacy of these apples is part of our community’s responsibility for the future of our regional agriculture.